The four Indianapolis Public Schools educators in Group 24 had a problem: their hypothetical school district was broke.

As part of an exercise at a meeting Wednesday sponsored by TeachPlus, small groups were asked to create a compensation plan for a fictional urban district with 45,000 students, 3,000 teachers and a $190 million budget, or somewhat bigger than IPS, which has about 30,000 students, 2,800 teachers and a $263 million budget.

The challenge was to redesign the way teachers were paid and earned raises by redistributing the way the money was spent. Nearly 150 IPS educators who attended quickly found the task wasn’t easy.

“Let’s see if we can find people who will work for free,” fifth grade teacher Sue Leibrock of IPS School 31 said sarcastically when Group 24’s 10-year projections showed a deficit.

Across the table, a similarly exasperated Sylvia Myles, a teacher at School 103, jokingly looked beyond the rules of the activity for help.

“We’ll just get a Title I grant,” she said, raising a chuckle from her teammates by referencing the federal funds that buoy budgets of schools with many poor students.

A good time for a frank talk about IPS’s spending

TeachPlus, an organization that aims to get teachers involved in education policy making, selects fellows each year to work on finding solutions to tough problems that face schools. The Indianapolis executive director, Caitlin Hannon, is on the IPS school board and formerly taught in the district.

To support a study of compensation by a pair of TeachPlus fellows, the organization brought in Education Resource Strategies, a Boston-based non-profit that consults with school districts to help them better utilize their resources. TeachPlus invited all IPS teachers to participate in the budget-making exercise.

For teachers, the budget problems posed by the activity are very real. Tight finances have caused mostly flat salaries over the past five years thanks to pay freezes. Even after Superintendent Lewis Ferebee announced the district finished 2013 in the black, declining revenue means the district could have less to offer when it begins negotiating a new contract with the teachers union this summer than they would like.

This year, the talks have an added dimension — the sides will be aiming to construct a new compensation system as required by a 2011 state law that mandated a statewide overhaul of the way teachers are evaluated and how those evaluations affect their pay.

Rachel Quinn, a fourth year teacher at Harshman Middle School and one of the TeachPlus fellows who organized the event, said she is eager for IPS to forge a better system of pay.

“My salary was frozen as second year teacher,” said Quinn, who also is active in the district’s teachers union. “I make what a first-year teacher makes. The net pay has been going down in IPS.”

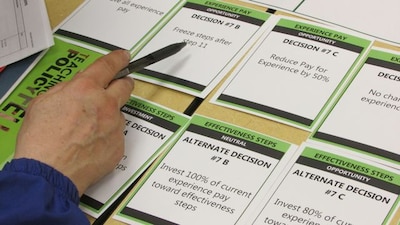

For the exercise, teachers in small groups were given cards with a series of policy choices — such as maintaing the union-backed “step” system of annual raises based on experience or new ideas like paying bonuses to the highest rated teachers — with price tags attached. Each group had to mix and match the policy options to assemble a compensation plan that fit within the fictional district’s budget over 10 years.

Pay and evaluation are emotional issues for teachers

TeachPlus, IPS and the teachers union all supported the exercise, sending email invitations to their members and every district teacher. Some of them arrived not knowing what to expect.

Walter Nordstrom, for example, said he joined TeachPlus and attends their events to learn more about the big issues facing education. Nordstrom was a 39-year-old retail manager six years ago when he took a magazine survey that suggested he was well suited for a career in teaching. After he was laid off a month later, he followed the survey’s advice and changed careers.

In the past, he’s found exercises like this one are often designed to lead the group to a predetermined outcome.

“If this wasn’t TeachPlus, I wouldn’t trust it,” he said.

Union leaders had their doubts, too.

“I didn’t know what to expect,” said IPS’s union president, Rhondalyn Cornett. “But I think it was an eye-opener for teachers.”

For a few teachers who came Wednesday to the district’s Forest Manor training center, just talking about how teachers should be judged and whether pay should be connected to their performance was very personal, and difficult. A few minutes into discussion in Nordstrom’s group, one of the four teachers at the table got up from her chair and walked out of the meeting. She said she couldn’t take it and didn’t want to get upset.

Her group members empathized.

“She’s taught for 43 years,” said Perle Washington, a social worker at School 114 the past five years. “She’s given her whole life to this and she feels like she has to beg for a raise. Money is always an emotional issue when you look at your livelihood and the stress you are under to perform.”

Along with Lori Harting, a physical education teacher at School 43, Nordstrom and Washington soldiered on, trying to construct a compensation system that maintained step increases — regular raises teachers get for additional years of experience or for taking more academic courses — but also gave something extra to the most effective teachers.

“The big thing we’re tripping over is the word ‘effectiveness’ and what that means,” said Nordstrom, who teaches in an IPS run alternative school at Lutheran Child and Family Services’ residential treatment center.

All of them wanted teachers to get good raises and make more money. The problem was how to pay for it. They saw the parallels to the situation for administrators and union leaders at IPS.

“I’m very concerned about what’s happening in the district,” Washington said. “I am caught in this pay freeze. I’d like to know how they’re going to look at giving us a pay increase and how they will evaluate us.”

She thought the exercise helped her better understand the district’s challenges.

“This puts it right on the table so I see it,” she said. “It makes it very real and makes us know we can participate and, from a knowledge point, really understand it.”

Struggling to save the traditional, union-preferred step system

If there was one thing the members of Group 24 were sure of, it was that they weren’t going to build a new system that didn’t include step increases for teachers.

Along with Leibrock and Myles, the group included Elvia Solis, a biology and forensic science teacher at Arsenal Tech High School; Jacki Sababu, a compliance monitor for special education; and Erin Hubbard, a McFarland School English teacher.

“I resent not getting paid for my experience and education,” Leibrock said. “I won’t vote for that.”

But the group did like some of the other policy options on the table, such as raising the district’s minimum pay for first-year teachers by $2,000 and giving extra pay for teachers who play important school roles, like chairing academic departments.

They quickly recognized that their numbers weren’t adding up. They would have to either drop some those extras or cut step increases.

Hubbard asked if the group would consider at least some changes to the step system. For example, ending the steps after 11 years would save a lot of money, making some of the other extras affordable. That would make raises for senior teachers entirely performance-based.

“It’s not what we want, but what if it saves us money and we have opportunities to use that elsewhere?” she said.

Leibrock wasn’t buying it. Experienced teachers were left too vulnerable to being stuck with stagnant wages if they were no longer guaranteed any raises after 11 years, in her view.

Solis had another idea: what if they didn’t eliminate raises that result from the steps but reduced some of them? For example, teachers who earn a master’s degree would still get extra pay for that, but half as much as they currently do.

The group agreed to try it, but the numbers still didn’t quite balance. To get there, they dropped a few of the extras from their original plan, such as tuition reimbursement for teachers and the $2,000 hike in starting pay.

That did it. They had a working system that came in under budget, maintained step increases with some reductions and added on a few new extras for teachers.

The group eased back in their chairs. It was a genuine accomplishment; other groups around them were still struggling to make their math add up.

Still, Group 24 hardly felt completely satisfied with its final plan.

“In the end we made decisions on what saved money,” Myles said with disappointment, “not on what we needed for teachers.”