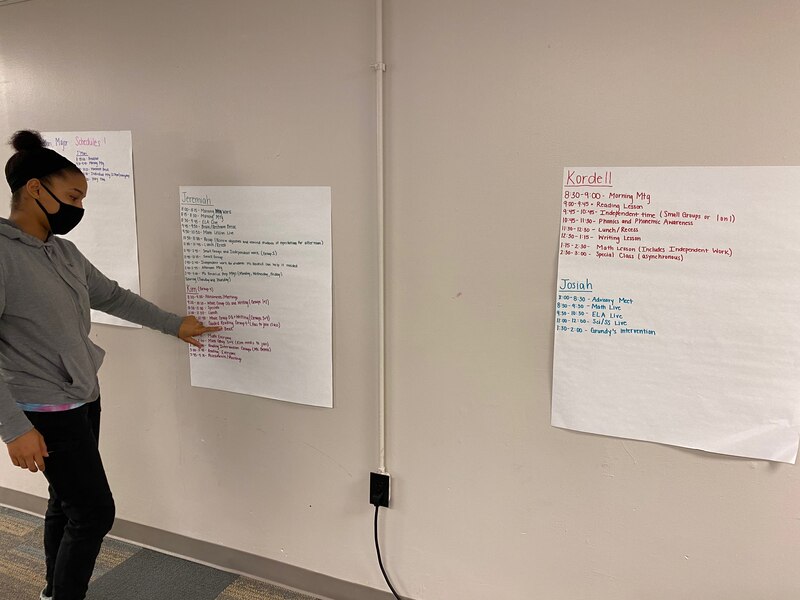

Amari Washington supervises nine children attending nine different virtual classes in a community center on the westside of Indianapolis.

She has so many schedules to track. So she tapes three big posters detailing who is doing what and when on the wall.

A student named Jeremiah starts his morning meeting at 8:15 a.m., but Kendra begins hers at 9:20 a.m. J’Mari has a break to move and stretch at 10 a.m. that lasts for 20 minutes, just as Jeremiah is in the middle of a live math lesson. At the same time, Kim has a writing group to attend.

“Some of them will be on(line), some of them will be off, some of them will have to go to lunch, some of them will still be in class,” Washington said, “We have to work together in order to make sure everybody is in class when they’re supposed to be.”

By “we,” she means the staff of Christamore House community center, one of Indianapolis’ 26 “community learning sites” offering safely designed supervision for children from kindergarten through 12th grade attending virtual school.

This is a new kind of environment for students and the Christamore staff.

After Indianapolis Public Schools, the state’s largest school district, decided to start the year virtually in August, The Mind Trust non-profit gathered funders for community learning pods, as these sites are commonly known. The 26 sites can serve up to 882 students — but the need could easily be in the tens of thousands, The Mind Trust officials said. About 45,000 students attend K-12 school in Indianapolis.

Sites like Christamore House fill the gap for vulnerable students who need a free, safe, supervised place to learn — particularly those from low-income families with parents who have to go into work — so that those children don’t fall behind.

Many students at Christamore House come from the area — Haughville, a working-class, predominantly Black neighborhood.

Each student in a pod is likely attending a different class from their pod-mate. The staff members, dubbed e-learning specialists, are not credentialed teachers, but they oversee student learning. Christamore House staff juggle the needs of 32 students across different grade levels from various schools, and also talk to teachers and parents, help students log into classes, and troubleshoot technology.

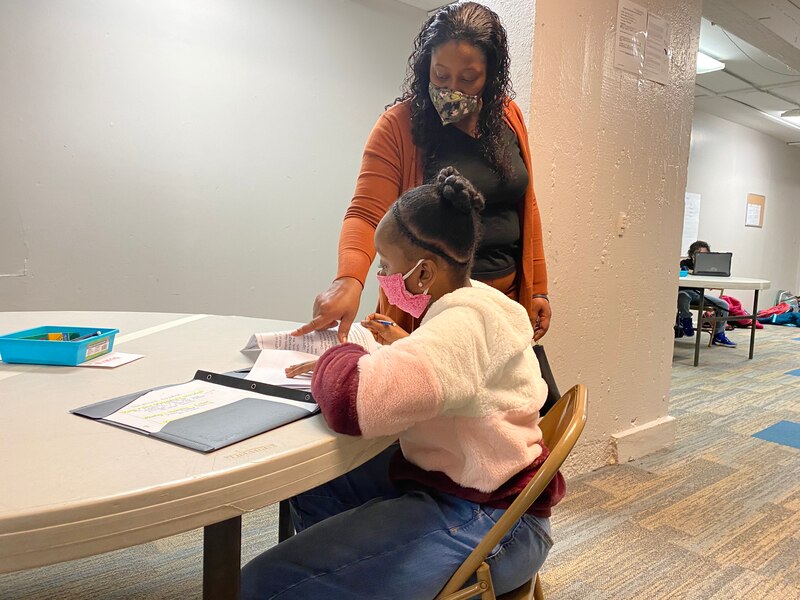

On a recent morning, Rochelle Brooks dropped off her 10-year-old daughter Tatiana. Brooks and her husband both work outside the home and don’t want to leave Tatiana alone.

Brooks stopped to tell the e-learning specialists that Tatiana had been missing a 1 p.m. class, thus hurting her grade and attendance.

The specialists reassured Brooks that they would log Tatiana in.

“1 o’clock today, we’re going to make sure we get on that one,” specialist Tori Curd said.

After students sign in at Christamore House and get their temperatures checked, specialists ensure everyone’s devices are charged. If they are, students get candy, a reward for coming prepared for learning. The students split into groups and go to different rooms.

Two students sit across from each other at each round table, logging into class via video, beginning work from a packet, or watching YouTube videos before class starts.

As Curd helped her students that day, she noticed one with special needs talking on screen with the teacher.

“Oh my goodness, he got into class,” Curd said. “I’m so proud of him this morning.”

Students can face technological difficulties. That day, a couple of students waited several minutes after class was supposed to start to be ushered into their virtual rooms.

One of the students Curd helped as she floated around the room was a second grader, Jeffery. For several minutes, he flashed a yellow card with a QR code toward his video camera so that his teacher would allow him into virtual class.

Curd made her way over to J’Mari, a 4-year-old with bright blue headphones, wearing a Captain America shirt and a sporty face mask that sometimes fell off his nose. He was lingering on YouTube.

“You got a few minutes, you see what time it is?” Curd asked J’Mari.

“It says 2!”

“8:53 a.m., so are you going to be able to log on?”

J’Mari eventually logged into class on time. His teacher asked the students to identify what’s in pictures she was showing. J’Mari shouted out answers, a blueberry muffin breakfast stuffed in his mouth.

If a problem arises, the e-learning specialists call or text the teacher or borrow student headphones to ask the teacher on screen what students are supposed to be doing.

Washington and Curd said they’ve seen teachers kick students out, sometimes for the rest of the day.

“We have to deal with it at that point,” Curd said.

If she feels discipline is not fair, she takes up the issue with teachers. She wants to make sure that none of her students gets left behind.

“No matter if you hate me, at the end of the day, I’m going to make sure you get this work done and that you get a good grade,” Washington said.

At the same time, Washington proclaims she’s a fun type of person and kids love being in her group.

Between the nine students’ schedules, she squeezes in time for jumping jacks, dancing, watching a movie, playing in the gym, or walking outside.

“This is not school,” Washington said. “You’re just here to do your schoolwork. I’m here to help. But I’m also here to have fun with you too.”