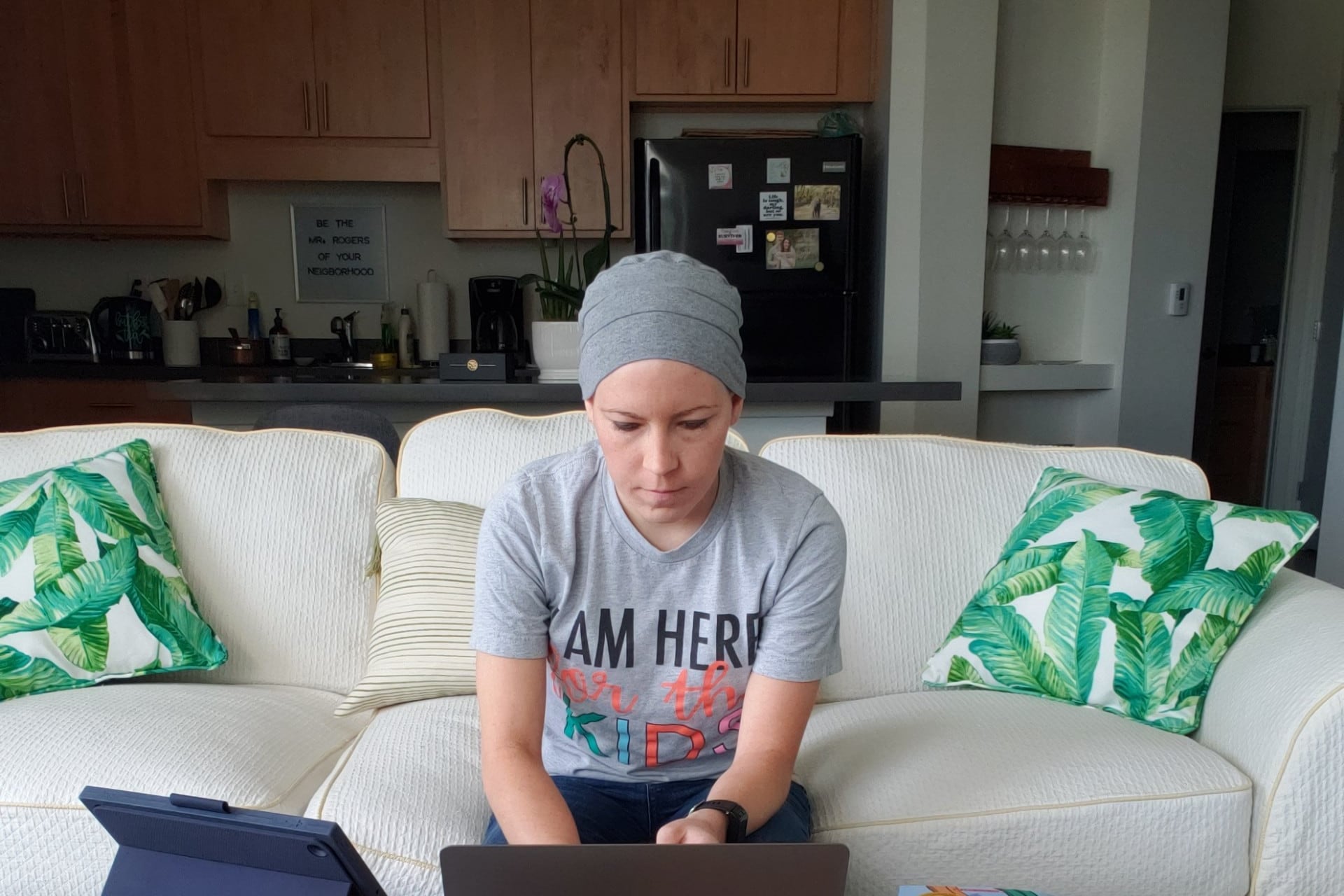

Three days a week, Katy Aiello starts her morning by video conferencing with as many as 25 fourth graders. From the couch in her apartment, the Grassy Creek Elementary teacher leads them through their morning routine. She calls on each student to share something with the group, then they play a game or she reads them a book.

It can be chaotic. So Aiello started teaching the 9- and 10-year-olds video meeting etiquette. She tells them to find a quiet place before joining, if possible.

Some students get on the call while sitting at a desk, notepad ready, she said. Others log on while still lying in bed under a blanket. Some have with them a younger sibling, whom they are watching while their parents are at work. A few students don’t show up at all. In those cases Aiello tries to make contact with a parent later on.

“I’m trying to toe the line [before] being intrusive and annoying,” she said.

The coronavirus quickly changed what teachers are expected to do, and it forced districts to redefine their jobs. Work hours extend beyond the school day, as teachers spend their time off learning new technologies and answering emails from families. Many also juggle caregiving responsibilities, such as helping their own children through remote learning.

What started as a scramble is poised to have a lasting effect, likely reshaping teacher contracts when negotiations begin in the fall, said Indiana State Teachers Association president Keith Gambill.

Until then, administrators and teachers must come to informal agreements for how to manage this new reality. Last month, teachers in South Bend filed a complaint with the state saying administrators violated their contract by making changes to teachers’ conditions without discussions with the union.

There’s no denying that a typical day for educators looks starkly different than it did just a few months ago. Hours of conversation with students have been reduced to minutes spent talking through a computer screen. Whiteboards have been replaced with hand-made backdrops in the corner of a living room. And hands-on activities have been replaced with simpler worksheets.

To understand how the coronavirus health crisis is changing what it means to be a teacher, Chalkbeat Indiana talked to a handful of educators around the state. Here’s what they said their days look like now.

10 a.m. — An unorthodox sendoff

Mondays aren’t e-learning days for teachers at Richland Bean-Blossom Schools in Ellettsville, Indiana. But the Edgewood High School English department uses the waiver day to hold their weekly meeting. Last week, colleagues told Lawrence DeMoss — who is retiring after 32 years — that he would want to record the next video call.

Since teachers couldn’t circle around a cake to celebrate DeMoss’ retirement, one-by-one they surprised him by telling him how much he meant to them and how he had impacted their careers.

“It brought tears,” he said. “It was a nice sendoff, and I wasn’t expecting that. I have a recording of it, which I have already shared with my sister.”

After teaching for more than three decades in Ellettsville — a small town nine miles northwest of Bloomington — DeMoss is trying to make his final days count, even under these unusual circumstances. For the past few years, DeMoss has announced seniors names as they walk across the stage during graduation. Now he’s working with the building principal to come up with something similar, but virtual, so he can still share in their milestone.

“I want to just do as much as I can with [my students] in the meantime,” he said. “And share as much of the graduation ceremony as I can.”

9 a.m. — Being sick means life feels ‘doubly stressful’ now

At Grassy Creek, Aiello said her workload feels lighter. The Warren Township teacher has shifted from plowing through new standards to largely focusing on review, following the district’s directions. The biggest portion of her time is spent collecting and organizing students’ work — however and whenever they manage to turn it in. For some students, that means texting a photo of a worksheet.

But she doesn’t welcome the extra free time, which leaves more room for anxiety. Aiello was diagnosed with breast cancer earlier this year. This month she will finish her last two rounds of chemotherapy before undergoing surgery over the summer.

“It is doubly stressful,” she said. “The only time I leave the house, really, is to go to the hospital. … I am very worried about getting sick and making anything worse.”

Were school buildings open, being around so many children would leave her more susceptible to getting ill. But she thinks it would also help her cope.

Instead, she looks forward to her 9 a.m. video conferences, scrounging up what supplies she has in her apartment to come up with a new game or lesson. Most of her books and materials are locked inside her shuttered classroom, so she gets creative.

On particularly high-energy days they do jumping jacks or a quick scavenger hunt — searching for a strange cooking utensil or an item that shares the same first letter as your name. Other days she reads them a story, the “mute all” button frequently coming in handy.

“I like that mute button,” Aiello said.

11 a.m. — Feeling the pressure to ‘step it up’

Online teaching doesn’t come naturally for Indianapolis Public Schools teacher Nathan Blevins, although he’s working hard to compensate. With so many public examples of teachers posting creative and inspiring lessons, there’s a lot of pressure.

“I’m going to be honest with you, I am not enjoying it,” Blevins said.

By the end of his prep time at 11 a.m., the eighth grade history teacher at Longfellow Middle School has usually tried to learn at least one new skill that will help him teach online. The first thing he taught himself was how to record his screen, so he could make more engaging videos for his students. Nothing fancy, but it “gets the trick done,” he said.

Becoming more creative is critical, Blevins said. Right now, only about 40% of his students complete their online school work each week. Part of the barrier for IPS students is access to a computer or the internet, but Blevins thinks better lessons will increase participation, even though they aren’t being graded as usual.

“I think I do feel some pressure to figure out how to step it up,” he said. “I had to sit back and go, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing.’ That really kind of helps you reframe everything, and realize it’s not the end of the world if everything is not perfect.”

7 p.m. — ‘I’m there for them’

Pike Township gives teachers a three-hour window when they must be available to answer students’ questions. For second grade Eagle Creek Elementary School teacher Anastasia Luc, it’s from 1-4 p.m. But if she’s being honest, she’s available much later than that.

“I’ll be sitting at night and I’ll hear my work email go off,and I’ll just go answer it anyway because I don’t care,” she said. “I just want my kids and my families to know that I’m there for them.”

Luc grew up with five siblings, so she can imagine what it’s like to try to share a computer to get schoolwork done. And she knows many of her second grade students have parents who are essential workers and can’t help keep with assignments until the evening.

With that in mind, she teamed up with other second grade teachers to develop assignments that are creative, but don’t require parental help. She’s asked her students read to their stuffed animals, challenged them to try a new chore every day for a week, and taught them how to make a puzzle, carefully cutting up their own drawing.

“There’s so much power in asking questions and setting goals and collaborating with other people,” Luc said. “My remote classroom is great, but it’s definitely not my own because I work with so many other great resources.”

Midnight — A classroom in a pickup truck

It was late by the time fifth-grade teacher Tim Conner wrapped up hours of work inside his pickup truck.

That afternoon he couldn’t get the internet to work at his Delphi home, which happens often. He and his wife, who is also a teacher, tried hotspots, but nothing was strong enough to allow them to download documents from their students at the same time.

So Conner loaded up his truck with his computer and books and drove a few miles to the Delphi Community Elementary School parking lot, where the district is providing free Wi-Fi. He got to work sitting in the car outside the locked building, sipping on the two Diet Cokes he picked up from McDonald’s. He took a break only to drive a few blocks away to use the restroom at a convenience store. His wife later joined him at the school parking lot.

Working from outside the school has become an afternoon routine once or twice a week, Conner said, but it was a particularly bad backlog of assignments that kept him out until midnight.

“It was a very frustrating day,” he said. “But I’m pretty fortunate. I live three miles from the school, so it’s not that big of a hassle. Once I reprocessed the way that I was doing things ... things have gotten better.”