Before COVID-19 forced his high school to close, Paris King was enthusiastic in algebra class.

Smart and outgoing, he was the kind of student who would vigorously debate whether to use the elimination method or graphing to solve an equation. Once he understood a concept, the ninth grader was quick to help classmates.

He put in extra time, coming to tutoring on Saturdays, said Erica Mellinger, his math teacher at KIPP Indy Legacy High School in Indianapolis.

But when the pandemic forced KIPP to close the campus nearly a year ago, he started to struggle. Watching recorded lessons alone, 14-year-old King stopped turning in some schoolwork. His grades plummeted.

Stuck at home, King was bored, he said. “We didn’t know what to do.”

The coronavirus unexpectedly left thousands of Indiana high schoolers in charge of their own education in a way they had never been before. Schools scrambled to make sure students had computers, internet, and access to lessons at home.

But even if they had those tools, instead of learning alongside others overseen by teachers, teenagers were expected to learn at home in the same environment where they played video games and hung out with family. For some, that version of school proved especially difficult.

Watching previously thriving students like King flounder alarmed leaders at KIPP Indy. Just weeks after schools closed last March, they came up with a plan: They would bring students who were struggling the most back to campus.

It was an exception that needed special permission from the county health department. The students still attended classes virtually — while teachers and classmates logged on from home. About 15 students participated from the school building in the Martindale-Brightwood neighborhood, supervised by staff.

“We can do the very best we can in a remote setting, but it’s impossible to replicate the level of support that we’re able to provide in person for students,” said Andy Seibert, executive director of KIPP Indy, which also runs an elementary school and a middle school. All are part of the KIPP national charter network.

Many school systems have prioritized bringing younger students back in person first, in part because they are less likely to get severely ill or to spread the virus, but also because of concerns that they struggle to learn remotely and parents need child care.

But the first students KIPP Indy decided to bring back were the small group of high schoolers who were rapidly falling behind. Those students simply have fewer years to catch up, Seibert said.

“The stakes are higher for high school students,” he said. “The older students get, the more important it is that they’re making progress and staying on track.”

Over the past year, spikes in COVID-19 cases have pushed Legacy to flip back and forth between fully remote learning and classroom instruction. But for much of that time, King has gone to school in person.

When the school year started, King would go to the Legacy campus, where a small group of students studied in the cafeteria. By January, students had moved to the KIPP elementary and middle school building, where a community center ran a remote learning site for KIPP students in all grades. Each morning, King’s mother dropped him off at the school on her way to work as a manager at a hotel.

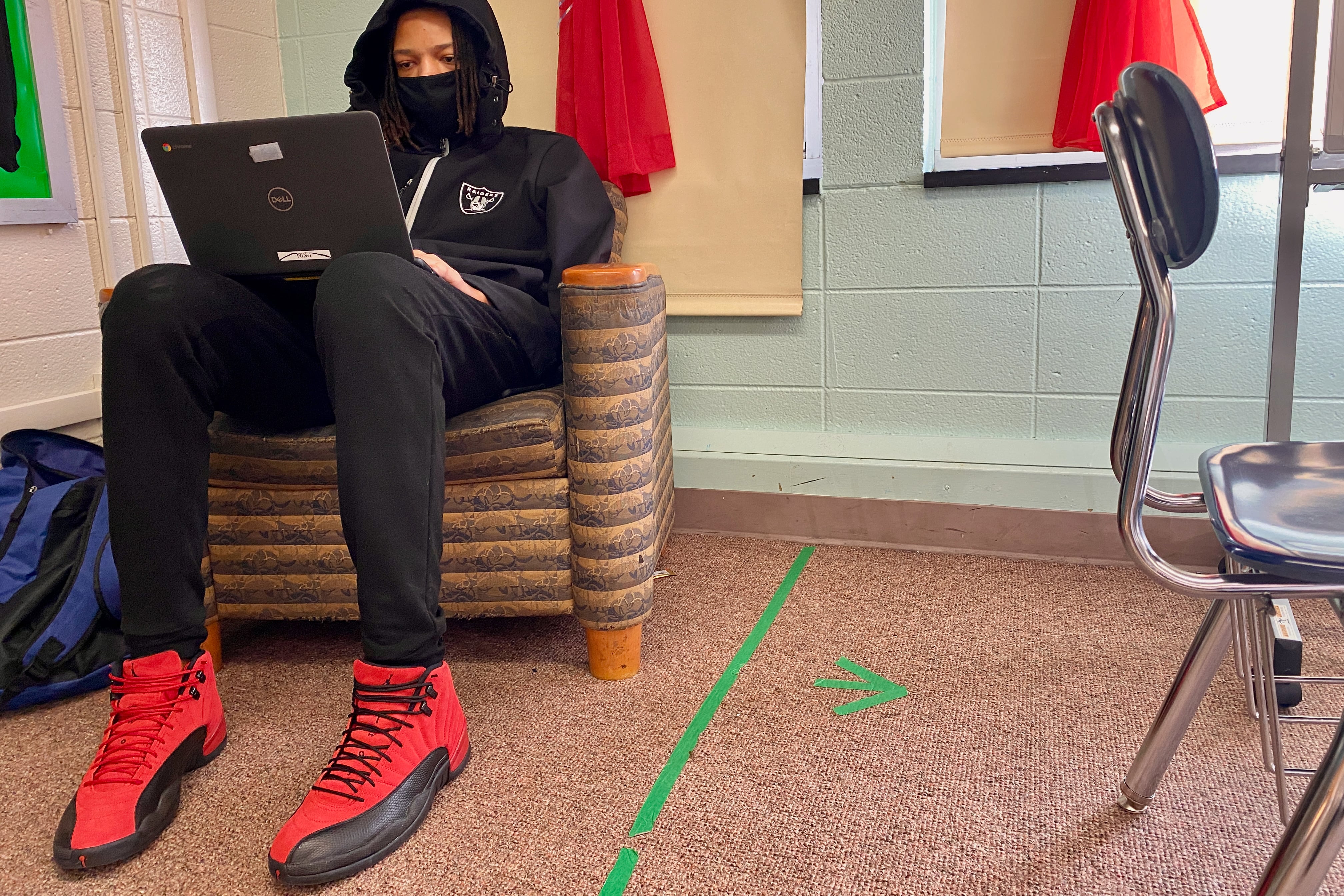

On a Thursday in January, King got to campus, sat down at a lunch table, and fell asleep at about 7:45 a.m. Just after 9 a.m., he slipped into the classroom where one other high schooler was sitting with their teacher. He found a spot in an armchair in the corner and quickly signed on to his remote history class.

At the remote learning site, Leeta Robertson, who usually teaches performing arts, oversaw a handful of high schoolers. Rather than teaching subject matter, Robertson helped keep students on track. She could watch their screens on her own laptop. If they were late to a virtual class, she reminded them. And if they had technical problems, she helped.

“It’s the school setting. So your mindset as a teenager is just totally different,” Robertson said.

Before he came back in person, King would try to do schoolwork at home with his older brother. But if he felt like his teachers were overworking him, he would stop, he said. Sometimes, he would just watch his younger cousin play video games.

At the remote learning site, it’s different.

“I’m more focused,” King said. “My game isn’t there to distract me.”

That Thursday, King sat at his laptop in the corner for world history. The teacher pressed students to describe a painting and what it revealed about French society before the revolution.

“Exactly, Paris, that’s going to be important,” said his teacher, as King typed his observations in the chat box.

When Legacy first closed the campus last March, students were supposed to watch prerecorded lessons from teachers. But educators quickly realized students weren’t engaged. This school year, video classes were live, so students could interact with each other and the teacher.

In this virtual class, King was attentive. Even when his phone beeped with an alert, he ignored it and continued typing in the assignment sheet.

That focus in class shows in King’s grades. After plunging last spring, his grade point average is now above 3.5. He seldom misses classes. In person and online, he interacts with teachers and other students, part of what he likes about school.

After history class ended, he stood up and walked around the room to chat with classmates.

“I kind of mess with them so they can wake up,” King said.

Principal David Spencer said King is a leader in class in a way that’s unusual for high schoolers: He makes sure others are participating. When students talk in small groups about class material, King not only answers questions but also helps pull answers out of others.

When COVID-19 first closed the campus, moments like that suddenly disappeared. But bit by bit, the school has been trying to bring them back.

Legacy recently revived a meeting that helped build community and get students excited about school. Before the pandemic, students started each morning by gathering in the cafeteria. School staff would shout out students who did well the day before, chanting and clapping. It generated a “camaraderie and spirit,” recalled Mellinger, the teacher for King’s advisory group, which meets before regular classes.

By late January, Legacy reopened in person, and about 60% of high schoolers returned to campus. Still, it’s impossible to have large assemblies safely in the middle of a pandemic, Spencer said. So last month, to spark some of the same enthusiasm, Legacy started weekly, virtual meetings.

In her advisory classroom, Mellinger projects the meeting on the smartboard. From home, students watch on laptops.

It’s King, at school in person, who uses the chat box to ask students at home questions — making sure they are participating.