James Whitcomb Riley School 43’s future changed merely by chance.

Edison School of the Arts was slated to take over the school in the fall. It would have been yet another change for the school that community members say was enacted by Indianapolis Public Schools without their input.

But Edison fell into chaos earlier this year, when parents accused its executive director Nathan Tuttle of using a racial slur, while students and staff said he created a hostile working and learning environment. Last month, IPS and Edison nixed the plan for Edison to run School 43 as an autonomous school in the district’s Innovation network.

Over the past decade, the major storyline of School 43 has been one of instability, high staff turnover, low test scores, and declining enrollment. But the collapse of Edison’s plan has left community members in the tight-knit Butler-Tarkington neighborhood with an unexpected, albeit small window of opportunity to change the trajectory of its K-8 school.

And this time, they say, it will be different: Instead of waiting for the district to drum up its latest fix for School 43, they’re making demands for exactly what they want for the school — and explaining how they plan to bring change themselves.

A group of advocates known as the Butler-Tarkington Education Committee have also submitted to the district their vision for School 43, and are working with the district on a memorandum of understanding about how to overhaul the school for at least the 2023-24 school year.

Essentially, their plan is to create a community-led school with a neighborhood school advisory committee and a coordinator in charge of community partnerships that already exist — such as tutoring, literacy efforts at the local community center, and the neighborhood’s mental health support center. Their plans, which they’re still developing and discussing with neighborhood residents, are similar to a model used by another IPS school community that banded together in 2017 to help run its own school without a charter operator.

“We’ve been patient,” said Sabae Martin, who graduated from School 43 more than 50 years ago and has worked for years to revive it. “And we’ve worked with them long enough to learn that unless we take the bull by the horns, we’re going to continue to get gored.”

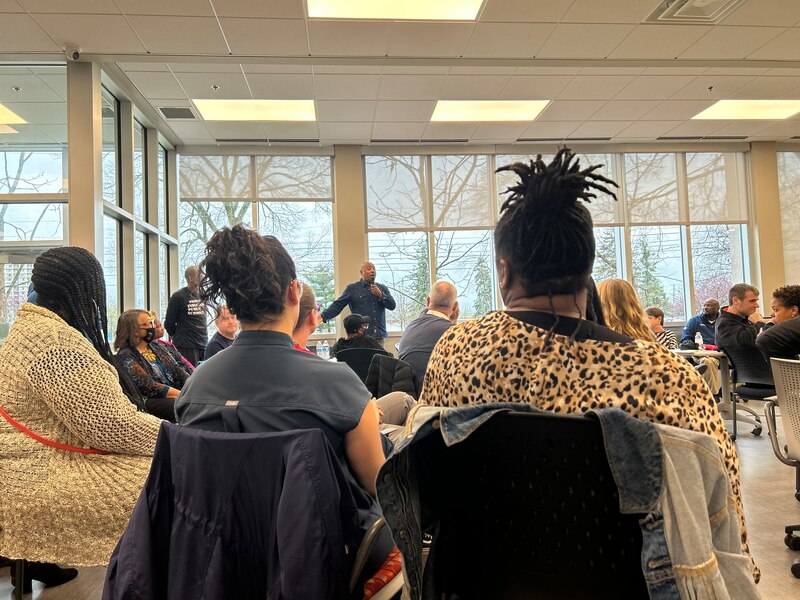

The district did not respond to a request for comment about School 43. But IPS school board member Hope Hampton, whose District 3 includes the school, told community members that they have her ear at a recent public meeting about the school.

Neighborhood seeks organized effort for community-run school

One window into the school’s troubles is its decline from an A rating with the state in 2012 to an F by 2016, a grade it retained through 2020, the last year the state used A-F letter grades for accountability. It cycled through five principals in a five-year period from 2014 to 2019.

Just 1.5% of students were proficient in both English and math on the state’s 2022 ILEARN test.

But the school has also enjoyed a strong web of neighborhood support for years. Butler University College of Education students help staff the library. A mentoring program through the National Council of Negro Women has helped middle school girls believe in themselves. Another alumna, Brenda Vance Paschal, helped launch a journalism program.

The community itself is anchored by a number of churches, the MLK Center, and lifelong residents.

The school has plenty of partnerships and caring organizations, said Jim Grim, a member of the committee who helps run the Indiana Community Schools Network, at a recent meeting.

“The missing ingredient,” he said, “is the coordination.”

Community schools across the country are based on the idea that the schools serve as neighborhood hubs for a variety of educational, family, and social services. The federal government’s Full Service Community Schools grant program, among other efforts, supports such schools.

In addition to its long-term plans for the school, the Butler-Tarkington Education Committee has a seat on the interview committee for the school’s new principal, which should be placed by the end of May, said Allison Luthe, executive director of the MLK Center.

The model that School 43 advocates are envisioning closely resembles the community-run model at Thomas Gregg School 15. There, community members and the John Boner Neighborhood Centers stepped in six years ago to take their neighborhood school into their own hands. Today, School 15 is one of the few Innovation schools in IPS that isn’t a charter.

Getting to that point took many community meetings and hard work.

But James Taylor, the CEO of the John Boner centers, said that process led the School 15 community to realize it could not only influence the school, but take ownership of what it provides to students and families.

Now, Taylor says, the school has community support embedded in the school that can direct families to services such as housing assistance or tutoring. The school itself has also become much more open to assistance from the community, Taylor said.

But the Thomas Gregg model might not work for School 43 and the Butler-Tarkington neighborhood, he added.

“We looked at our ingredients, and we ended up at Thomas Gregg,” Taylor said. “Their community needs to explore what kinds of ingredients they have and make their own recipe.”

And some Butler-Tarkington community members bristle at the mention of becoming an Innovation school, a term that for many means becoming a charter. Notably, Thomas Gregg is not run by a charter operator.

How the community gets IPS on board with its desires, however, is “the $64,000 question,” said Vance Paschal, who like Martin graduated from School 43 over 50 years ago.

“We first want them to be accountable and to listen and to just trust us, since we have trusted them and they have failed,” she said. “We’re on the ground. They’re like the generals out in D.C., we’re the troops out here who are fighting.”

Staff need help with student behavior, parental involvement

The school’s challenges inside classrooms underscore community concerns.

Staff at the school said they’re dealing regularly with behavioral issues among students and need more people in the building.

Endia Dunner, the school’s assistant principal, said at the recent meeting that teachers are running themselves ragged. Having more people in the short-staffed school to provide more support would boost teachers’ own mental health and morale, she noted.

”They just need a little bit of time so that they can make sure they stay healthy for themselves, for their own families, so that they can continue to come back day after day after day,” Dunner said.

Johnnie Rivera, a parent at the school, said his son struggles in class because of distractions.

“He says the teachers have to keep pulling the kids out of the classroom because of the kids behind him keep acting up,” he said after the community’s first town hall. “And he’s like, sometimes, I can’t learn nothing because they have to keep stopping.”

Rivera said he’s thought about transferring his son to a different school if it doesn’t get any better.

Hampton told community members at the meeting that she hoped to hear from them so she could be an advocate for the school as well.

“It’s sad to hear some of the things that you’re dealing with, but the commitment and the passion means everything,” she said.

Residents hope efforts to restore School 43 will help more than the school itself.

“It’s possible it can come back,” said Martin. “And you know what, we’re going to end up with a better neighborhood because of it.”

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Marion County schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.