Indiana’s 2023 legislative session is under way, and state legislators have introduced more than 100 new education bills and bills impacting schools and students. For the latest Indiana education news, sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free newsletter here.

This article originally published on WFYI.

The House Education Committee heard hours of testimony Wednesday from school employees, librarians, and others across Indiana who expressed opposition to a proposed amendment to a bill that would strip these employees of a legal defense against charges they distributed material harmful to minors.

The hearing was the latest evolution in a months-long legislative process driven by concerns among some parents that pornography is rampant in schools. While lawmakers have drafted legislation to address these concerns, they’ve presented little evidence to suggest it’s a widespread problem. The latest iteration of the legislation also targets public libraries.

Rep. Becky Cash (R-Zionsville), who crafted the amendment, said she’s heard from “thousands” of parents who have lodged complaints with their schools over books they believed were objectionable.

“Parents have testified in school board meetings and come to me, and many members of this committee and assembly many, many times over the last couple of years saying that the system did not work for them,” Cash said.

She explained that the amendment mandates schools and public libraries lay out a transparent process for parents and residents to lodge complaints.

But several Democratic members of the committee expressed concern that the bill would empower some parents and disempower others by creating a system in which some parents could control access to books for all children. They also expressed opposition to a portion of the amendment that strips librarians and school employees from a legal defense.

“We are not the court of appeals from parents who are unhappy with school board decisions,” said Rep. Ed DeLaney (D-Indianapolis). “But if we were the Court of Appeals, we would want evidence. What parent? What school? What book? What hearing? What process? Not this vague discontent.”

Changes to the language made

An amendment to Senate Bill 380 incorporates some of the language included in Senate Bill 12 — which was passed by lawmakers in that chamber in late February. SB12 would have mandated schools adopt a procedure that would allow parents and guardians to submit complaints that a book included in the school library is inappropriate. The legislation laid out a specific procedure and an appeals process.

In contrast, an amendment to SB 380, crafted by Cash, would require schools to adopt and publicly post a procedure that would allow district residents, parents and guardians to submit a request for removal of material that is classified as obscene or harmful to minors as defined by existing state law, as well as an appeals process.

The amendment would also require:

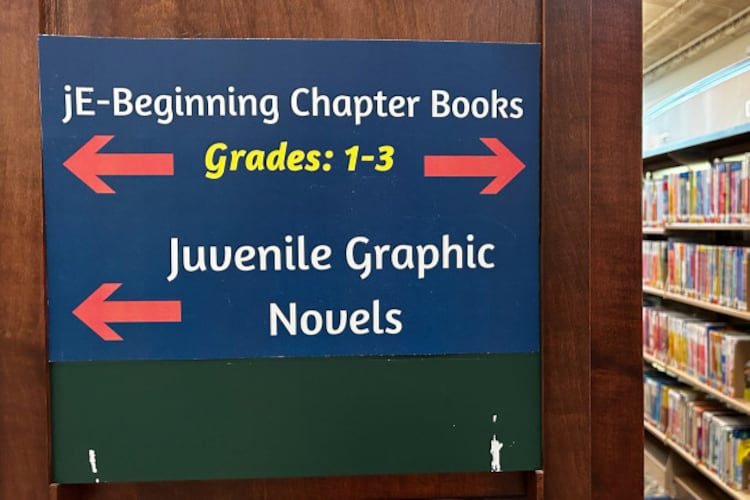

- Public libraries to adopt and publicly post a procedure that would allow community members, as well as parents and guardians of minors within their community, to submit a request to relocate material that falls under the definition of obscene or harmful to minors — as defined in current law — to a section of the library not designated for minors.

- Both schools and libraries must adopt a procedure to respond quickly to these requests and allow for an appeal. And the procedure they adopt must require school and library boards to review the relocation request at their next public meeting.

- Prosecutors consider whether residents, parents or guardians have exhausted these procedures before filing charges against a school or library employee for disseminating material harmful to minors.

- School and public libraries make all available book titles publicly available in an online catalog.

Bill would eliminate statutory defense

Under the amendment to SB 380, if a prosecutor charged a school or public library employee with disseminating material that is harmful to minors, the employees would be unable to defend themselves on the basis that the material had educational value.

The amendment also appears to bar school and library employees from using the defense that the material was disseminated while acting within the scope of their employment.

Few people testified in favor of the amendment in its entirety. And while many of the librarians who testified said they supported the portion of the legislation that mandated a procedure for requesting removals or relocation of books, they all opposed the language that removes the criminal defense against prosecution.

“Criminalizing librarians, library workers and teachers is not the answer, “said Heather Rayl, a librarian at the Vigo County Public Library. “What is right for my daughter may not be right for your daughter or son or niece or nephew, even if they’re the same age. Parents know best it is their right to choose. Not the government.”

Zach Stock, with the Indiana Public Defender Council, also spoke out against removing legal defenses for school and library employees. He emphasized the need to protect legitimate expression.

“We can’t all agree on what is harmful. None of us in this room are going to agree to that. There’s no bright line,” Stock said. “The public defender counsel asks that you leave the criminal code out of it. A felony jury trial is no place to conduct education policy.”

Disagreements persist over what constitutes harmful material

Librarians and others also expressed concern that regardless of whether the change in law results in prosecutions, it could still have a chilling effect on the types of materials librarians choose to put in school and public library collections — particularly when it comes to books that deal with racism, gender, sexuality and those that feature individuals from marginalized communities.

Specifically, lawmakers and those who testified sparred over the appropriateness of the book, “Gender Queer,” a graphic novel written and illustrated by Maia Kobabe, that recounts the author’s exploration of their gender identity.

Austin Rawlins, a 22-year-old, spoke out against the amendment on behalf of his mother, Stephanie Rawlins, director of the Pike County Public Library. He said he found more value in the book “Gender Queer” than he did in much of the sex education content he was exposed to in school, like images of sexually transmitted diseases and video of someone giving birth.

Rep. Martin Carbaugh (R-Fort Wayne) acknowledged that he hadn’t read “Gender Queer” in its entirety. But he challenged Rawlins for comparing the book’s “depictions of fellatio and many other acts” to sex education.

“I don’t even know how periods work. I don’t know what’s going on in a woman’s body, because it’s never [been] taught to me. It never is, it’s never discussed,” Rawlins said about topics not covered in his sex education courses. “And these books are honestly the first time that I’ve seen it in a relatively educational way or life experience way.So I find value in that.”

Carbaugh responded by saying he disagreed.

Katie Blair, Director of Advocacy and Public Policy at ACLU of Indiana, said the amendment would infringe on student’s rights to read and learn freely. She said the language could be used to target books that are about or by people of color, LGBTQ individuals and other marginalized people.

“A person can decide that they don’t want to read a certain book, a person can decide they don’t want their child to read that book, but a person can’t decide an entire school or an entire town can read that book,” Blair said

Rep. Jake Teshka (R-South Bend) questioned how the language in the amendment about obscene material would apply to books about communities of color.

“What we also know is that there’s still a lot of room for interpretation. And so what I would say is that this will be used as that because those books, unfortunately, are usually under much higher scrutiny,” Blair said. “And so I know that this is what that will be used for.”

Rhonda Miller was one of the very small number of people who testified in support of the measures included in the amendment. But Miller, who presides over a group called Purple for Parents Indiana that traffics in conspiracy theories and anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, expressed disappointment that the language had been included in SB 380 rather than being heard as a standalone bill under SB 12.

“I want everybody to know that this battle is far from over. And we will continue the fight,” Miller said.

The House Education Committee did not vote on the amendment. April 17 is the last day for Senate bills to be approved by the full House.

Contact WFYI education reporter Lee V. Gaines at lgaines@wfyi.org. Follow on Twitter: @LeeVGaines.