Liliana Ortuno turned to SUPER School 19 as her last hope.

She had shuffled from school to school trying to find appropriate language services for her two daughters, who didn’t speak English. After her oldest daughter’s stints at William Penn 49 and SENSE charter school, a friend finally directed Ortuno to the innovation school within Indianapolis Public Schools — a frequent recommendation among Latino families on the southeast side.

After the switch, Ortuno’s eldest daughter’s reading ability improved. When her youngest daughter was diagnosed with anxiety, she took advantage of the school’s mental health services, which offered therapy twice a week. Now, her sessions are shorter because of her improvement.

But all of that may soon be gone.

Under the district’s proposed revitalization plan known as Rebuilding Stronger, IPS would end its innovation agreement with SUPER School 19. Nearby Paul Miller School 114, which is being closed at the end of this school year, would merge with School 19 as the district resumes control of the school. Those two big changes could alter, curtail, or end the programs that Ortuno values.

At its core, the district’s Rebuilding Stronger plan seeks to create an equitable education for all students. Some see the blueprint as a significant and obvious step forward for academics and other programs. But to others, Rebuilding Stronger aims for equity in an inequitable way.

Some parents of color, for example, worry the plan’s replication of things like International Baccalaureate programming won’t serve their students as well as other models. Other families fear losing a school that has served a Black neighborhood for generations.

The plan, which the IPS school board is slated to consider for a vote Nov. 17, would close underutilized schools and reconfigure grades, with the aim of boosting resources at all the remaining schools. It would expand academic programs such as Montessori and IB into schools with more students of color. And in a boon for school choice, Rebuilding Stronger would allow students to attend any one of a variety of schools within one of four zones.

Two miles away from SUPER School 19, Garfield Elementary School 31 sits half empty.

The school has lost nearly half of its students since she came in 2016-17, and that has affected its operations. Fewer students means fewer per-pupil dollars, fewer staff, and fewer academic opportunities for students.

“I have probably two kids upstairs who are ready for algebra,” said Principal Adrienne Kuchik, “and I can’t offer it to them.”

To staff like Kuchik, Rebuilding Stronger would fix many inequities she’s seen in her neighborhood school. She’s hoping that enrollment at her school, and therefore resources, would rebound. But more broadly, she’s excited by the idea that under Rebuilding Stronger, students in her school’s neighborhood would have more options like Center for Inquiry and Montessori schools.

“With this proposed idea of enrollment zones, not only will every family have access to all these different types of programming, they also have transportation to all of these different types of programming,” Kuchik said.

Losing a school that helps English learners

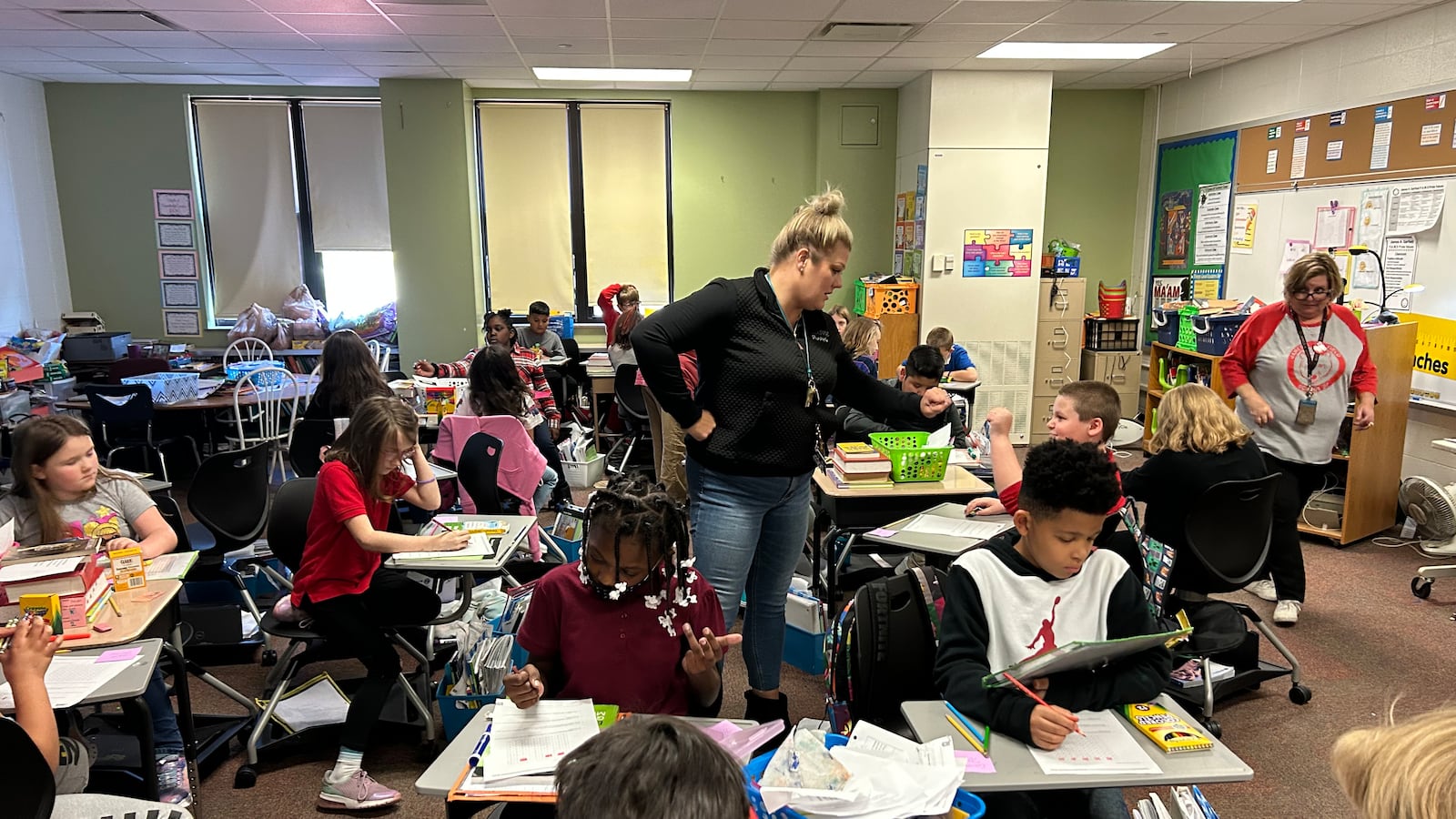

Spanish flows at the front office of SUPER School 19 as quickly and easily as English.

The school began as an innovation school in 2018-19 and was given more autonomy than traditional district schools.

Ortuno and fellow mother Jaquelinne Vazquez Rodriguez don’t speak English, but they’re well known in the building as active parents.

This community taught their children English. It also helped Vazquez Rodriguez when her husband faced deportation. Staff wrote letters to a judge that supported keeping her family together, Vazquez Rodriguez explained.

The district wants to end its innovation partnership with SUPER School due to its poor academic performance. The school had an IRead passing rate of roughly 84% the year before its transformation, a rate that has dropped to about 30%. ILearn scores have also dropped, from roughly 8% of students proficient in English and math in 2018-19 to just 3% in 2021-22.

They feel uncertainty about whether losing the school principal will stay, and whether the services such as the mental health therapy Ortuno’s daughter received would remain.

“I’m an adult. A change like this causes anxiety,” she said. “I can’t imagine what it’s going to do to someone who is still small.”

But Ortuno and Vasquez Rodriguez feel their concerns — which had to be translated — weren’t heard at the school’s recent meeting about the plan. Both feel, too, that the school is uniquely positioned to serve their children’s mental health and language needs.

There’s another side to the situation. The merger would provide a better facility for School 114 students currently stuck in a building rated in poor condition. Combining both schools would solve the problem of dwindling enrollment at School 114, which has dropped by more than half since the 2015-16 school year. And moves like this would also help alleviate the district’s budget woes.

“We know that our long-term financial sustainability just will not exist if we don’t do something different than what we are currently doing,” Superintendent Aleesia Johnson said when unveiling the plan to the media in September, adding “that “the current mix of data and programming that we have are not sustainable.”

Families fear end of neighborhood school

Steps away from the front door of School 56, a yard sign with a petition to save the school sits in Barbara Brooks’ front yard.

School 56 sits tucked away in Hillside, within range of the gentrification moving east from the popular Monon Trail. The school is a fixture in the community, an area that has been home to Black residents since the neighborhood’s industrialization at the turn of the 20th century, according to Indy Encyclopedia.

Brooks, 67, went to the school with her siblings — as did her children, grandchildren and now her great-grandchildren.

But today the school is underutilized, operating at just 59% of capacity last school year. The building, erected in 1931, is in poor condition. Under Rebuilding Stronger, the district recommends merging the students at School 56 with nearby School 51, which will adopt Montessori programming.

The district walked back its initial proposal to tear down School 56 and built a new school for Sidener Academy for High Ability Students after community pushback of gentrification fears.

But the changes to the initial Rebuilding Stronger plan — unveiled by the district last month — don’t alleviate all concerns. Parents hope to still keep School 56 open as a neighborhood school and seek funding for renovations, so that the Martindale part of Martindale-Brightwood won’t lose its last traditional public school.

“At one time there were three schools in that neighborhood,” said DeShawn Jorman, a parent who started the petition to save School 56. “Now there’s only one left — 56. And now we’re not going to have a school there, period?”

Parents wonder why the district can’t just renovate the school, like it has in more affluent, white areas.

District officials say compromises in such situations have been necessary.

“As Dr. Johnson has said throughout this journey, we can do a lot of things but we can’t do everything,” school board President Evan Hawkins said last month. “I think that resonates in a plan like this.”

Tension simmers over two school models

The replication of certain academic models is also a point of contention.

Organizations that have embraced charter schools such as Stand for Children Indiana and Empowered Families have objected to the plan’s expansion of Center for Inquiry and Montessori models.

Parents of color affiliated with such groups have criticized the gap in proficiency levels between Black and white students or Hispanic and white students — particularly at CFI schools, where the IB curriculum is taught. They have also expressed reservations about the ability of these schools, where the students are mostly white, to teach students of color.

Many parents have instead pushed for the replication of Paramount charter school, where Black students’ proficiency rates in English and math on 2022 state tests range from 29.6% to 66.7% across three brick-and-mortar campuses — well above the district’s 5.1%.

Angelia Moore, the incoming at-large school board member who won election on Tuesday, has also expressed reservations about expanding such programs.

When her youngest son needed extra academic attention as a CFI student, she felt that he was not offered enough support and fell through the cracks, she said.

“As a mother of Black boys, catching up is not really okay,” Moore said.

She ultimately decided to home-school her son after noticing the limited number of staff who were people of color.

The plan replicates Montesorri, CFI, Butler Lab, performing arts, dual-language and high-ability programming currently at 14 schools.

Of those schools, seven have a measurable Black-white achievement gap that’s greater than the district-wide average — as measured by proficiency in English and math on the 2022 state ILEARN exam. Six have a measurable Hispanic-white achievement gap greater than the district average.

Yet students of color at some of these schools perform better than their peers districtwide: Black students in nine schools and Hispanic students in eight schools have proficiency rates higher than the district-wide average.

Paramount’s four campuses still had better proficiency rates for Black and Hispanic students than the majority of these schools.

District leaders’ concerns about expanding Paramount in particular extend beyond test scores. Johnson also noted the suspension rates at Paramount schools are higher than the district’s CFI schools.

“We can both acknowledge that on the whole, Black and Latino students are performing better [at CFI and Montessori schools] and therefore having that program be accessible to more students is important,” Johnson said, “and address, acknowledge, and know we have to continue to work incredibly hard to address that gap that exists.”

Expanding access for south side students

When Emma Wulf started band at George Washington High School she was in a new school trying to learn something new — her previous K-8 school did not offer band programming. Fortunately she conquered her fears, she told the school board last month.

“If we were able to start band programs in middle schools, this could help high school experiences be less scary and more of a safe place when in a new community,” Wulf said.

Currently, neighborhood schools like the one Wulf attended have just one-third the number of enrichments — such as arts and world language — as choice schools, according to the district.

And on average, IPS middle schools offer nine athletic programs, while neighboring townships offer 13, the district has noted.

But closing schools and reconfiguring grades would allow the district to concentrate its resources in remaining schools, offering more academic and extracurricular programming for students like Wulf.

Under the plan, Garfield Elementary would shift from a K-8 to a pre-K-5 school.

Dropping the middle grades will be sad, Kuchik notes — but that means filling up the partly empty building with elementary students from nearby schools such as Raymond Brandes School 65, which is proposed for closure. And the middle-schoolers she’s losing will have more opportunities elsewhere, she believes.

“Where my babies are going, they’re going to have the option of foreign language. They’re going to have the option of band. They’re going to have the option of — I would assume — choir or chorale, things that I can’t (offer) like pre-algebra and algebra by eighth grade,” Kuchik said.

And adding prekindergarten at her school will bring a program that families have been asking for, she said.

Although she ultimately supports the plan, Johnson has acknowledged that it would require different sacrifices from different school communities that may be difficult.

“While we can all recognize that change presents opportunities, change is also hard,” she told the community in September. “Both of those things are true.”

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Marion County schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.