This story is part of a partnership between Chalkbeat and the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica. Using federal data from Miseducation, an interactive database built by ProPublica, we are publishing a series of stories exploring inequities in education at the local level.

When Christopher Sanders was in kindergarten, his teacher told his parents that the bright, kind boy should take the test to get into a gifted program.

Particularly adept at math, Christopher breezed through school easily and seemed to need extra challenges. But when he took the test, Christopher didn’t score high enough to be considered for a high ability program at his school in Warren Township, an Indianapolis district where white students are nearly 2.5 times as likely as black students to get into such tracks, according to state data.

“A lot of times black boys aren’t given the opportunity to show they can excel — but given the opportunity, they can,” said Christopher’s mother, Ericka Sanders, who appealed the results and got her son a seat.

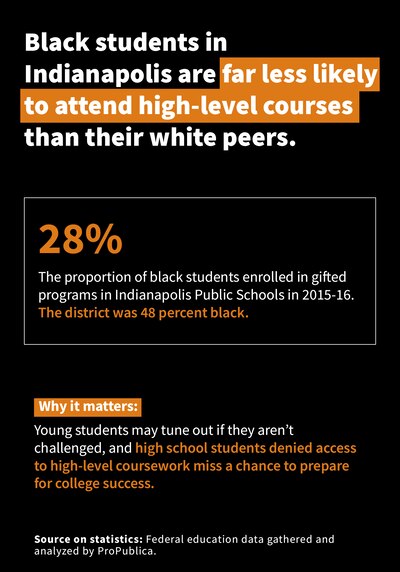

She’s right to be worried that he faces obstacles other children might not. Across the nation, in Indiana, and in most Indianapolis districts, black students are far less likely than their white peers to be in gifted and talented programs or take advanced high school classes.

In Indiana elementary and middle schools, white students are three times as likely as black students to be enrolled in gifted programs, state data from 2016-17 show. In high school, white students are twice as likely as black students to be enrolled in Advanced Placement classes, according to federal education data, newly compiled by the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica in an interactive database.

The gap widens in Indianapolis, whose school districts serve mostly students of color. In Indianapolis Public Schools, where most children come from families in poverty and schools have long struggled academically, white students are 3.5 times as likely as black students to be in high ability programs and take advanced high school coursework, the data show.

The worst gap persists in one of the city’s wealthiest districts, Washington Township, where white students are eight times as likely as black students to be in high ability programs, according to the data, and four times as likely to be in Advanced Placement classes.

In some Indianapolis districts, the gap has prompted ongoing changes to how children are chosen for gifted programs. With policies such as universal screening, and a greater focus on training teachers, the diversity of Indianapolis Public Schools’ gifted programs is inching toward looking more like the district’s demographics.

The effects of limited access to accelerated work can compound over the course of a student’s school career. Students who aren’t exposed to advanced work early on can be steered away from or poorly prepared for Advanced Placement courses in high school, even if they can choose to opt in then.

“We need to stop thinking about victory as getting them to grade level,” said Jonathan Plucker, a professor at Johns Hopkins University who studies gifted education.

It’s difficult to pin down exactly why the gaps are so wide, but research into the question has offered some possible explanations. In some cases, educators’ biases could be keeping them from recognizing the potential of black children or poor children — which is exacerbated by the lack of black teachers, who are more likely than white teachers to see black students as gifted, according to one study. Screening systems might not be evaluating students in an equitable way, especially if children are chosen for assessment.

“When they’re performing at the same level, some kids are getting in, when others get left out or overlooked,” said M. René Islas, executive director of the National Association for Gifted Children. “There are systemic barriers to allowing these students in.”

But local officials and experts agree that some schools are making headway in addressing these inequities, in part because of a growing awareness of the problem. In Washington Township, where the city’s greatest disparities exist, schools spokeswoman Ellen Rogers said in recent years the district has been training teachers to be more culturally responsive, build relationships with students, and focus on individual student performance. “We recognize the challenge nationally of improving the AP participation of our students of color,” she wrote in an email.

Indianapolis Public Schools has made incremental progress in increasing the proportion of black and Hispanic students in high ability programs, according to Candace Huehls, the district’s high ability coordinator. Additionally, Huehls said the district’s data differs from the state’s data, showing smaller racial disparities among advanced students.

The district uses several strategies that are considered best practices for identifying students for high ability programs. All students are screened in first and fifth grades, Huehls said. Top scorers and students nominated by parents, teachers, and administrators are given tests to measure their ability and achievement. Those tests results determine who qualifies for high ability programs.

Indianapolis Public Schools considers students for high ability programs based on where they fall compared to their peers within the district, rather than stacking them up against state or national standards. The district has also been training teachers on strategies to identify students who are advanced in math, English, or both subjects.

Identifying high ability students is critical at a young age, she said, because if they’re not challenged in school, they’re at risk for disengaging and checking out. Plus, high ability programs put students on track to continue with advanced classes throughout their education, including Advanced Placement classes in high school.

“It’s an area that we’re definitely still working on,” Huehls said, “but I think we’ve made some big improvements in educating teachers that all students have potential.”

Every school in Indianapolis Public Schools has some kind of high ability program — which experts say helps equalize opportunities.

“I think that’s important, because it sends the message to everyone in that school that we have talented kids here,” said Plucker, the Johns Hopkins professor. “I personally don’t hear that in a lot of urban schools. I hear the opposite.”

The programs may be in for further tweaks. Indianapolis Public Schools is evaluating its high ability programs this year, Huehls said, with the expectation of making “significant changes” next year.

She declined to elaborate on what the changes could entail, but she said the evaluation includes looking closely at the role of Sidener Academy, a district school specifically for gifted students. The school’s population is whiter and more affluent than the district’s overall demographics, in part because the school’s northside location is too far away from students in other parts of the district, Huehls said. It ends up filling unclaimed seats with students from nearby, and less diverse, suburbs.

Huehls, though, acknowledges that poverty makes it difficult to fully eliminate the racial disparities among the district’s high ability students. Students who move often can miss chances for screening, and students from low-income families often have less access to early childhood, after-school, or enrichment programs that can make giftedness more apparent to educators.

“Until we cure poverty and we get rid of discrimination, excellence gaps are not going to disappear completely,” Plucker said. “But lord knows they can be a lot smaller than they are right now. They’re just massive.”

One district school, Lew Wallace School 107, is on the front lines. Having seen a rise in students from around the world, school leaders worked to recognize high ability in students of color, non-native English speakers, students in poverty, and students coming from diverse educational backgrounds.

The elementary school uses a daily 30-minute literacy block and small-group instruction — made possible by a wealth of student-teachers and a training program where multi-classroom leaders support teachers — as “elevators” for high-ability students to pursue more challenging work while teachers to work with students who haven’t yet mastered grade-level skills.

“We have that mindset as a school: We’ll meet you where you are,” said Principal Jeremy Baugh.

On a recent day, a third-grade math class on multiplication broke into four groups. One, with the most advanced students sitting on the carpet with a student-teacher, practiced flashcards. At a table, the teacher watched lower-level students calculate answers on white boards. On the other end of the classroom, a visiting college student drew arrays with students. In a corner, an independent group moved clothespins on a chart.

The school also encourages enrichment opportunities that are usually more accessible to more affluent students, such as math club or robotics club.

Districts say the screenings for high ability students and training for teachers to serve high-ability students can be costly, but well worth the expense.

The state provides a little extra funding for high ability programs — a total of $13.5 million available statewide, with $500,000 dedicated to identifying students. The state also spends about $5 million each year to pay for students to take Advanced Placement exams and provide training for teachers.

Beyond access to advanced coursework, students also need the support to excel. In addition to gaps in access, Indianapolis schools also see disparities in who succeeds in Advanced Placement classes in high school. White students are more likely to take an AP exam than their black or Hispanic classmates — and they’re also much more likely to earn passing scores, according to state data.

These statistics and these challenges are precisely why Ericka Sanders fought so hard to have her son Christopher considered for his school’s gifted program.

“If we didn’t fight for that — if we had accepted the answer — we would’ve been doing him a disservice,” Sanders said.

Christopher thrived with the challenges of the high ability program at Warren Township, she said, and remained in high ability classes when the family moved to Lawrence Township.

Still, at the beginning of this year, as Christopher was starting fourth grade, his parents met with his teacher. They wanted her to know from the outset that they had high expectations for their son, and that they wanted him to succeed. They wanted her to know that they would be involved — and that they would support their son, and support her.

“I wanted to make sure he wasn’t underestimated,” Sanders said. “We prepare him at home: He’s prepared to go to school and learn and be respectful and listen and be a leader, and we want to make sure that same respect is in return.”

Correction: Oct. 22, 2018: A previous version of this story called Washington Township the wealthiest district in Indianapolis. It is among the city’s wealthiest districts, but it does not have the highest proportion of students who do not qualify for free or reduced-price meals, a measure of poverty.