An Indianapolis mother is suing the Indiana State Board of Education over a policy that sought to prevent brick-and-mortar schools from facing funding cuts when students were educated virtually due to the coronavirus.

Letrisha Weber, who has two children who attend virtual schools in Indiana, argued that a rule to fully fund students who attend remotely because of the pandemic violates several laws and is unfair to children who were already enrolled in virtual schools.

The suit seeks to increase money for online-only schools that existed before the pandemic by threatening the funding bump that the state awarded schools that shifted to remote learning due to the coronavirus.

Indiana typically provides 85% of the per-pupil allocation for virtual school students. With the rise of virtual education this fall, school leaders were afraid state support would plummet. To stave off cuts, the state board used emergency powers to approve a widely supported policy to increase per-pupil funding for students who would normally be in classrooms but are learning online because of the pandemic.

The new policy left funding at 85% for students such as Weber’s, who were already enrolled in online programs last year or students who transferred to virtual charter schools.

“The timing of when the student went online determines the ‘worth’ of the student and some students are worth 15% less than others,” Weber said in a press release from the Indiana Chapter of the National Coalition for Public School Options. “In my opinion, all students are equal and should be funded equally.”

The coalition lobbies in support of virtual schools. In a September letter to the state board arguing that the proposed virtual funding policy was unfair, Weber said she was the chair of the Indiana chapter of Public School Options and a member of the board of the national coalition.

Virtual schools have traditionally received less money in Indiana, and lawmakers further cut per-student funding for virtual schools in 2019 after years of dismal performance. A year ago, a special investigation by state auditors found that officials from two Indiana virtual charter schools misspent more than $85 million in state funding.

The complaint, filed this week in the Marion County Superior Court, names the Indiana State Board of Education and Executive Director Brian Murphy. It calls for the court to invalidate the rule and prevent the state from appropriating money under it “until the General Assembly fully and fairly allocates funding for all public school students.”

The spokeswoman for the Indiana State Board of Education declined to comment on pending litigation.

The lawsuit claims the rule fully funding schools exceeds the state board’s rulemaking authority, goes beyond the scope of the governor’s emergency order, and violates the equal protection provisions of the U.S. and Indiana constitutions.

But one legal expert said the plaintiffs are unlikely to prevail.

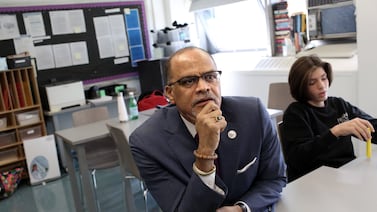

“My guess is this lawsuit will be quickly dismissed,” said Brad Desnoyer, an associate professor at Indiana University’s McKinney School of Law.

It made sense for the board to maintain funding for schools that would have faced a funding cliff because those campuses still had fixed costs for maintaining buildings, he said. Fully virtual schools simply don’t have the same expenses.

For the courts to overturn an agency rule, it must be considered “arbitrary and capricious,” Desnoyer said.

“This is not an arbitrary rule. This decision was made to keep our schools funded,” Desnoyer said. “What she’s asking for is so detrimental to the students of Indiana that I don’t see it happening.”

The purpose of the lawsuit is to boost funding for fully virtual schools, not to reduce funding for brick-and-mortar schools, Ann Coriden, the Columbus attorney representing Weber, wrote in an email.

“This lawsuit is not about reducing funding for others. Ms. Weber would like the legislature to fully and fairly fund all public school students, including her children,” Coriden wrote. “The rule adopted by SBOE creates a situation where two students at the same school receiving the same education can be funded at different levels. Ms. Weber does not believe her children are worth only $0.85, when another student participating in the same program is worth $1.00. This is patently unfair and should be addressed by the legislature.”

When the state board made the funding change in September, it relied on special power granted by the governor during the pandemic. But the board did not make the same change for spring funding, because staff said its authority was limited to a public health emergency and it was unclear whether the outbreak would improve.

Five months later, with thousands of Hoosier students enrolled virtually and the pandemic unabated, lawmakers have pledged to keep school funding intact.

The same day the lawsuit was filed, the Indiana House approved a bill that would continue the policy of fully funding some virtual students for the spring semester. The change must be approved by the Senate and the governor before going into effect.